Pinched Nerve / Impingement

Pinched Nerve/Impingement

A pinched nerve is a common complaint in people seeking medical care. Also known as nerve impingement, a pinched nerve can occur at nerve roots coming from the spine, or in other areas like the wrist and ankle. In either case, it often results in pain and/or numbness and tingling in an arm or leg. Luckily, symptoms are usually treatable with conservative care and don’t require surgery. It’s important to know what to look for, however, because the symptoms aren’t always what you might expect.

What is a Pinched Nerve?

A pinched nerve, or nerve impingement, goes by different names when occurring in different areas of the body. When a nerve root is compressed at the spine, it’s called radiculopathy and is usually caused by degenerating bone or disc. When a nerve is impinged in the arm or leg, it’s called entrapment or compression. To better understand how nerve impingement affects the body, let’s examine the function of nerves.

How Do Nerves Work?

Nerves are our master communicators. They take information from the brain and send it to the rest of the body, and vice versa. The ultimate goal is to maintain a state of balance in the body called homeostasis. Nerves communicate in various ways, triggering sensory and motor reactions to protect the body. For instance, when you touch a hot stove, the nerves in your skin send signals to your brain at lightning speed that danger is present. Your brain responds by sending a burning pain to sensory nerves in your hand, while simultaneously sending a message to your motor nerves to pull your hand away. Nerves, in a nutshell, keep us alive and well. Unfortunately, they are the primary source of pain, too. Peripheral nerves, or nerves that connect our brain to our body, originate as nerve roots exiting the vertebrae from the spinal cord. From here, they branch out and supply, or innervate, muscles to help us move, sensory areas to help us feel, and autonomic areas to activate our fight-or-flight and rest-and-digest responses. When something puts pressure on a nerve root, it affects everything the nerve branches out into. Compression of a nerve root can cause weakness, numbness, tingling, and dull, nagging pain. Irritation of a nerve root can cause sharp, shooting pain, burning, and hypersensitivity.

Types of Nerve Impingement

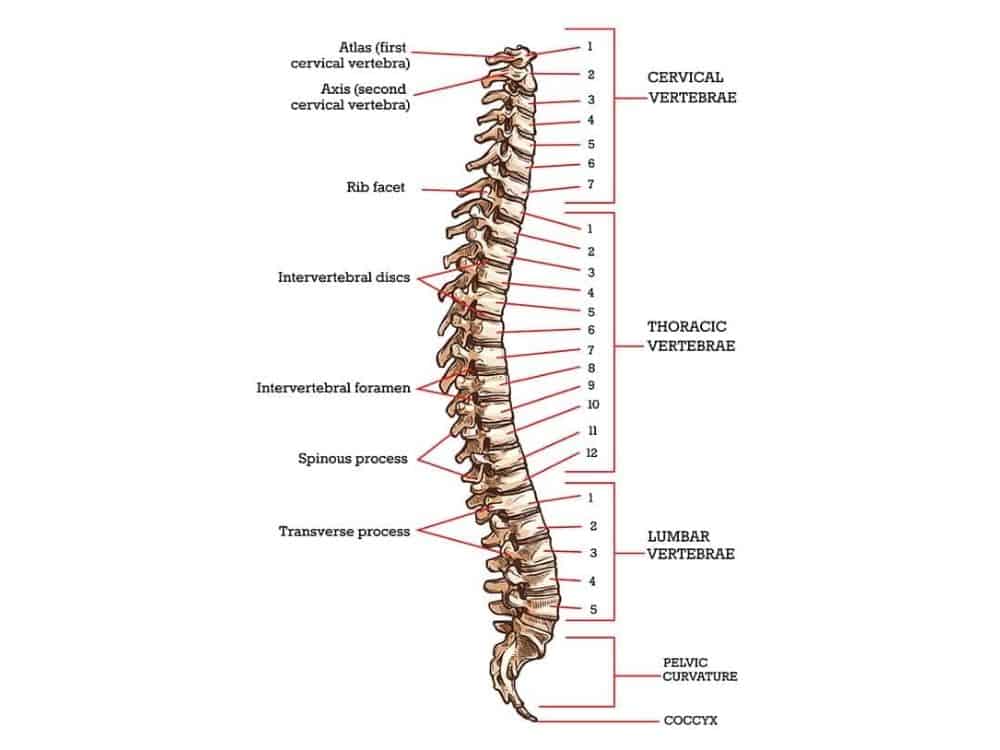

Nerve root impingement at the spine (radiculopathy), can occur at any of the 3 main spinal sections: cervical, thoracic, and lumbar. Nerve roots in the neck, or cervical spine, primarily affect the arms (upper extremities). Nerve roots in the midback, or thoracic spine, affect the trunk and ribcage. Nerve roots in the low back, or lumbar spine, affect the low back and legs (lower extremities). Pinched nerves can also occur in other areas of the body. Think about when you wear tight shoes to a wedding and feel a tingly sensation in your feet by the time dinner is served. You end up kicking your shoes off to dance after dinner because a nerve in your foot was being compressed. Common areas of nerve entrapment are the carpal tunnel at the wrist and tarsal tunnel in the ankle.

Cervical Impingement

How Does it Happen?

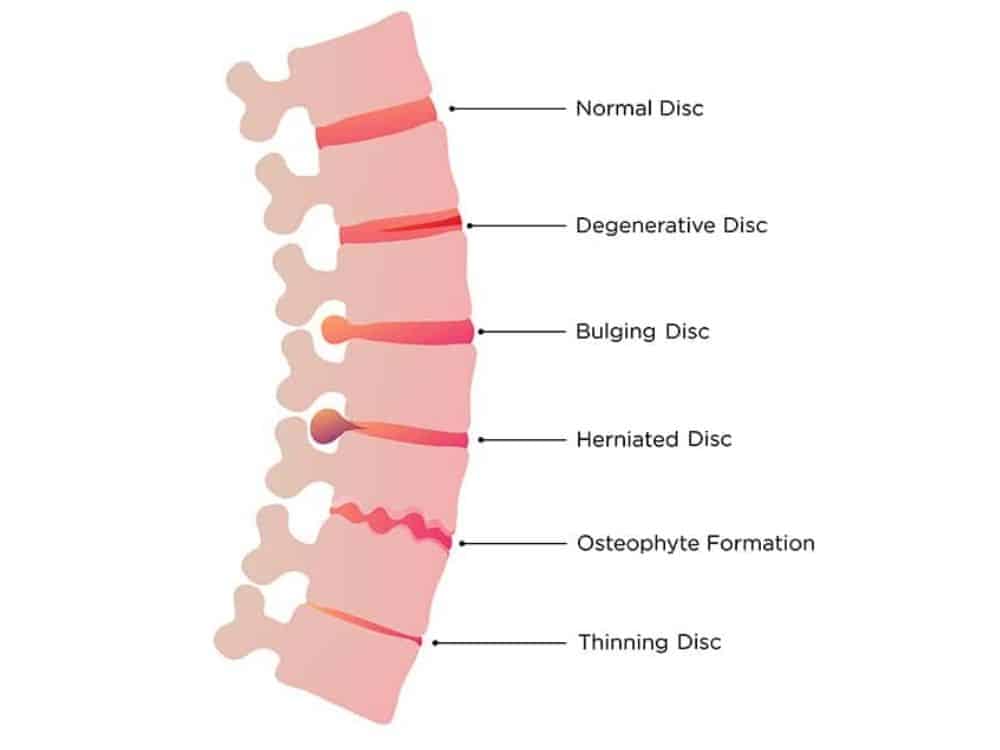

A pinched nerve in the neck, or cervical radiculopathy, occurs when a nerve root is compressed by herniated disc material, a degenerating disc, or aging bone. The body activates the inflammatory response, which causes swelling around the nerve root. This ultimately leads to pain and changes in nerve function.

While internal changes in the neck are the culprit for a pinched nerve, there are often external events that trigger the symptoms to follow. These inciting factors can contribute to the onset of pain with cervical radiculopathy:

- Poor posture

- Trauma (such as car accident)

- Sleeping in uncomfortable positions

What are the Symptoms?

A person with cervical radiculopathy may have symptoms in one or both arms and feel pain and/or numbness and tingling. Symptoms may go all the way into the fingers and follow a dermatome, or sensory nerve root pattern. Neck movements may be painful, the affected arm might feel weak, and the muscles around the neck may be tight. A clinician will likely do in-office testing to rule in the diagnosis, but unless trauma has occurred, further testing is not usually needed. If conservative treatment fails, an X-Ray or MRI may be considered.

How is it Treated?

Most cases of cervical radiculopathy resolve with conservative (nonoperative) management. In fact, in a five year follow up study of patients who had conservative treatment, 90% of patients were symptom-free or only had mild symptoms. Conservative treatment starts with medication, which can include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxers, opioids for acute pain, and antidepressants for chronic pain. Physical therapy may be prescribed to stretch the neck muscles and strengthen the postural muscles. The physical therapist may also use manual therapy or spinal manipulation to help reduce muscle tightness, joint stiffness and pain. Mechanical traction may be used, where the neck is intermittently placed in decompressive positions. If symptoms persist, an epidural injection may be considered. Only if all these fail is surgery considered. The most common procedure for relieving a pinched nerve is an anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion.

Thoracic Impingement

How Does it Happen?

Thoracic radiculopathy, or nerve impingement in the thoracic spine, can be caused by degenerative disc disease, rib dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, and placement of spinal cord stimulator. Since it is more rare in the thoracic spine than in the cervical and lumbar spine, thoracic radiculopathy can get overlooked among clinicians. In addition, symptoms of thoracic radiculopathy can mimic heart attack, lung problems, cancer, or other visceral organ dysfunction, making it important for doctors to rule out those conditions first.

What are the Symptoms?

People usually report radiating pain around the ribcage and in the trunk region. Pain may be present in the back near the shoulder blade (scapula) or in the lower abdominal region. Numbness and tingling may also occur, and it can feel painful to take a deep breath.

Treatment

Like nerve impingement in the neck, thoracic radiculopathy typically resolves with conservative management; medications to reduce pain and inflammation, physical therapy to stretch muscles and correct postural imbalances, and activity modification are the first lines of defense. If these methods don’t improve a person’s symptoms, then a procedure called percutaneous vertebroplasty may be considered. In cases of progressive symptoms and neurologic compromise, surgery is necessary.

Lumbar Impingement

It goes by many names—sciatica, lumbar radiculopathy, lumbosacral radiculitis, radicular pain, and pinched nerve, to name a few. This literal “pain in the rear” can be a nuisance, and in some cases debilitating. Spinal nerves are tricky, and a pinched nerve in your back may feel like pain in your foot. Let’s examine why this happens.

How Does it Happen?

Dysfunction of a spinal nerve root in the lumbar spine (low back) is the cause of lumbar radiculopathy. When one is compressed or irritated, a person will develop symptoms of a pinched nerve. Depending on the severity of the compression, the nerve may be affected along its entire course through the body, which is sometimes down to the feet. Here are some common causes of lumbar radiculopathy:

- Bulging disc

- Herniated disc

- Lumbar facet overgrowth (hypertrophy)

- Spondylolisthesis

People can develop this condition from direct trauma or chemical irritation to the nerve root, inactivity, staying in certain positions too long, using poor body mechanics with lifting, or having weak core musculature. Regardless of the cause, it is important to get an accurate diagnosis in order to treat it correctly. Lumbar radiculopathy, like thoracic radiculopathy, can mimic other conditions, which require different treatments. In rare cases, lumbar radiculopathy can be caused by infection, cancer, vascular disease, or congenital abnormalities. Therefore, quality evaluation and diagnosis from a physician is vital.

What are the Symptoms?

The classic symptoms of lumbar radiculopathy are pain and/or numbness and tingling extending down the leg, with or without accompanying back pain. The compromised spinal nerve root results in pain, weakness, and/or impairment of sensory regions associated with the affected nerve root. The muscles of the back, hip, thigh, and calf may be tight or feel like they are in spasm. This is more likely a result of irritated nerve rather than actual muscle tightness. Typically, the symptoms worsen with certain positions or activities, such as sitting or standing for long periods. Sometimes even lying flat to rest can increase symptoms. When the bones in the spine undergo the aging process, the spaces for nerves and the spinal cord to run through may narrow (spinal stenosis) and impinge nerves on both sides. In these cases, people can experience pain, heaviness, and/or numbness and tingling in both legs while standing upright or walking, which is called neurogenic claudication. The most commonly affected nerve with lumbar radiculopathy is the sciatic nerve, which is where sciatica gets its name. Symptoms specific to impingement of nerve roots of the sciatic nerve are pain and/or numbness and tingling starting in the low back, then radiating into the buttocks, and shooting down the back of the leg into the foot. This can be confused with piriformis syndrome or hamstring syndrome, which also affect the sciatic nerve, but not at the nerve roots. Often people with lumbar radiculopathy experience no back pain but have numbness and tingling in their legs and feet, which explains why people might not initially consider the low back as the source of their pain. It can feel like peripheral neuropathy, diabetic neuropathy, or Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome. However, these conditions are distinct from lumbar radiculopathy and should be treated as such. Neuropathy describes damage to or disease of peripheral nerves, which are outside the spine. Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome, as discussed later, is caused by compressed nerve in the foot. Other more serious conditions should also be ruled out in cases of numbness and tingling in the feet, such as Guillain-Barre Syndrome, autoimmune disease, and infection.

Treatment

Treatment for lumbar radiculopathy, like in the rest of the spine, is symptom-based. In the early stages, the primary goals are to reduce pain and restore any loss of sensation. This can be accomplished through medications, epidural injections, application of topical analgesics, and education on staying active/exercise. Physical therapy can help with reducing neural tension (pain caused by nerve irritation), releasing muscle tightness, and improving strength in core muscles. Research has shown that core musculature weakens during episodes of low back pain, which increases vulnerability to future episodes of radiculopathy. Mechanical traction and spinal manipulation may be used by physical therapists or chiropractors and can relieve symptoms in the short-term. Surgery may be used to decompress a nerve or fuse an unstable spinal segment. While statistics show that lumbar surgery is safe and effective in short-term, it has shown no long-term benefits for pain and function.

Other Types of Impingement

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome is nerve compression at the wrist. Here, the median nerve passes through bones and tendons and can become entrapped. Sitting at a computer for extended periods increases the risk, which may explain why it is the most reported nerve entrapment syndrome. It is also the most expensive upper extremity disorder in the United States, costing over $2 billion annually. In addition to desk job workers, others at increased risk are industrial workers and elderly. Symptoms include numbness and tingling in one or both hands, weakness of the hands and fingers, and wrist stiffness. Treatment includes activity modification, splinting, ergonomic modifications, occupational therapy, injections, and in serious cases, surgery. When evaluating, clinicians should rule out neck problems, as they can mimic carpal tunnel syndrome.

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Though much less reported than carpal tunnel syndrome, tarsal tunnel syndrome is a nerve entrapment syndrome that often goes undiagnosed because it gets missed. The posterior tibial nerve travels behind the inner ankle bone, where three other ankle muscle tendons also pass through. In anatomical terms, this is called the tarsal tunnel. In the tunnel, the nerve branches into three segments. When compressed, it can cause pain and/or numbness and tingling in any or all three segments, which affect the ankle and foot. Treatment includes physical therapy for stretching tight structures that may be compressing the nerve, strengthening weak muscles to avoid compensations, injection, and surgical release if necessary. Perhaps most important in treating this issue is getting an accurate diagnosis, as it may be assumed to be a pinched nerve in the back.

If you are experiencing pain that you want to discuss further, please make an appointment with Dr. Connor.